Predictive Sales Analytics: Use Machine Learning to Predict and Optimize Product Backorders

Written by Matt Dancho

Sales, customer service, supply chain and logistics, manufacturing… no matter which department you’re in, you more than likely care about backorders. Backorders are products that are temporarily out of stock, but a customer is permitted to place an order against future inventory. Back orders are both good and bad: Strong demand can drive back orders, but so can suboptimal planning. The problem is when a product is not immediately available, customers may not have the luxury or patience to wait. This translates into lost sales and low customer satisfaction. The good news is that machine learning (ML) can be used to identify products at risk of backorders. In this article we use the new H2O automated ML algorithm to implement Kaggle-quality predictions on the Kaggle dataset, “Can You Predict Product Backorders?”. This is an advanced tutorial, which can be difficult for learners. We have good news, see our announcement below if you are interested in a machine learning course from Business Science. If you love this tutorial, please connect with us on social media to stay up on the latest Business Science news, events and information! Good luck and happy analyzing!

Challenges and Benefits

This tutorial covers two challenges. One challenge with this problem is dataset imbalance, when the majority class significantly outweighs the minority class. We implement a special technique for dealing with unbalanced data sets called SMOTE (synthetic minority over-sampling technique) that improves modeling accuracy and efficiency (win-win). The second challenge is optimizing for the business case. To do so, we explore cutoff (threshold) optimization which can be used to find the cutoff that maximizes expected profit.

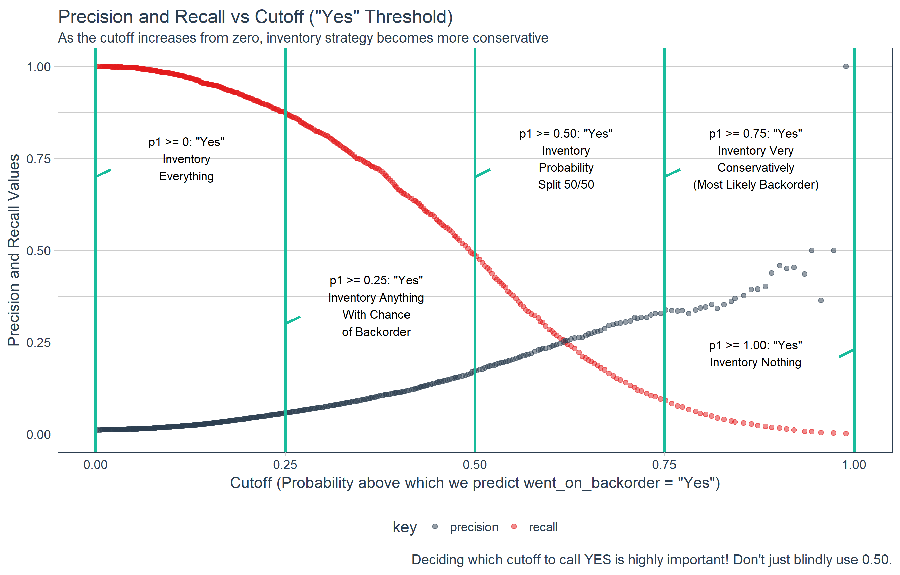

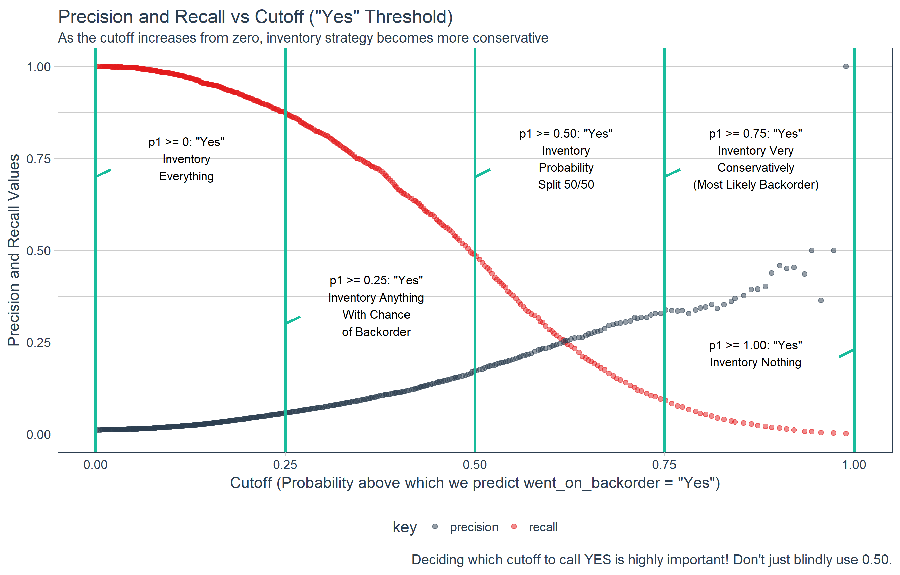

One of the important visualizations (benefits to your understanding) is the effect of precision and recall on inventory strategy. A lever the analyst controls is the cutoff (threshold). The threshold has an effect on precision and recall. By selecting the optimal threshold we can maximize expected profit.

Quick Navigation

This is a longer analysis, and certain sections may be more interesting based on your role. Are you an Executive or a Data Scientist?

- Executive: Read these:

- Data Scientist: Read these:

Others should just read the whole thing. ;)

Background on Backorder Prediction

What is a backorder?

According to Investopedia, a backorder is…

A customer order that has not been fulfilled. A backorder generally indicates that customer demand for a product or service exceeds a company’s capacity to supply it. Total backorders, also known as backlog, may be expressed in terms of units or dollar amount.

Why do we care?

Source: www.trustedreviews.com

A backorder can be both a good thing and a bad thing. Consider a company like Apple that recently rolled out several new iPhone models including iPhone 8 and iPhone X. Because the initial supply cannot possibly keep up with the magnitude of demand, Apple is immediately in a “backorder” situation that requires customer service management.

On the positive side, backorders indicate healthy demand for a product. For Apple, this is a credit to strong brand recognition. Customers are likely to wait several months to get the latest model because of the new and innovative technology and incredible branding. Conversely, Apple’s competitors don’t have this luxury. If new models cannot be provided immediately, their customers cancel orders and go elsewhere.

Companies constantly strive for a balance in managing backorders. It’s a fine line: Too much supply increases inventory costs while too little supply increases the risk that customers may cancel orders. Why not just keep 100,000 of everything on the shelves at all time? For most retailers and manufacturers, this strategy will drive inventory costs through the roof considering they likely have a large number of SKUs (unique product IDs).

A predictive analytics program can identify which products are most likely to experience backorders giving the organization information and time to adjust. Machine learning can identify patterns related to backorders before customers order. Production can then adjust to minimize delays while customer service can provide accurate dates to keep customers informed and happy. The predictive analytics approach enables the maximum product to get in the hands of customers at the lowest cost to the organization. The result is a win-win: organizations increase sales while customers get to enjoy the products they demand.

Challenges with Predicting Backorders

One of the first steps in developing a backorder strategy is to understand which products are at risk of being backordered. Sounds easy right? Wrong. A number of factors can make this a challenging business problem.

Demand-Event Dependencies

Demand for existing products are constantly changing, often dependent on non-business data (holidays, weather, and other events). Consider demand for snow blowers at Home Depot. We know that geographically-speaking in Northern USA the winter is when demand will rise and the spring is when demand will fall. However, this demand is highly dependent on the level of snowfall. If snowfall is minimal, demand will be low regardless of it being winter. Therefore, Home Depot will need to know the likelihood of snowfall to best predict demand surges and shortfalls in order to optimize inventory.

Small Numbers (Anomalies)

If backorders are very infrequent but highly important, it can be very difficult to predict the minority class accurately because of the imbalance between backorders to non-backorders within the data set. Accuracy for the model will look great, but the actual predictive quality may be very poor. Consider the NULL error rate, or the rate of just picking the majority class. Just picking “non-backorder” may be the same or more accurate than the model. Special strategies exist for dealing with unbalanced data, and we’ll implement SMOTE.

Time Dependency

Often this problem is viewed as a cross-sectional problem rather than as a temporal (or time-based) problem. The problem is time can play a critical role. Just because a product sold out this time last year, will it sell out again this year? Maybe. Maybe not. Time-based demand forecasting can be necessary to augment cross-sectional binary classification.

Case Study: Predicting Backorder Risk and Optimizing Profit

The Problem

A hypothetical manufacturer has a data set that identifies whether or not a backorder has occurred. The challenge is to accurately predict future backorder risk using predictive analytics and machine learning and then to identify the optimal strategy for inventorying products with high backorder risk.

The Data

The data comes from Kaggle’s Can You Predict Product Backorders? dataset. If you have a Kaggle account, you can download the data, which includes both a training and a test set. We’ll use the training set for developing our model and the test set for determining the final accuracy of the best model.

The data file contains the historical data for the 8 weeks prior to the week we are trying to predict. The data were taken as weekly snapshots at the start of each week. The target (or response) is the went_on_backorder variable. To model and predict the target, we’ll use the other features, which include:

- sku - Random ID for the product

- national_inv - Current inventory level for the part

- lead_time - Transit time for product (if available)

- in_transit_qty - Amount of product in transit from source

- forecast_3_month - Forecast sales for the next 3 months

- forecast_6_month - Forecast sales for the next 6 months

- forecast_9_month - Forecast sales for the next 9 months

- sales_1_month - Sales quantity for the prior 1 month time period

- sales_3_month - Sales quantity for the prior 3 month time period

- sales_6_month - Sales quantity for the prior 6 month time period

- sales_9_month - Sales quantity for the prior 9 month time period

- min_bank - Minimum recommend amount to stock

- potential_issue - Source issue for part identified

- pieces_past_due - Parts overdue from source

- perf_6_month_avg - Source performance for prior 6 month period

- perf_12_month_avg - Source performance for prior 12 month period

- local_bo_qty - Amount of stock orders overdue

- deck_risk - Part risk flag

- oe_constraint - Part risk flag

- ppap_risk - Part risk flag

- stop_auto_buy - Part risk flag

- rev_stop - Part risk flag

- went_on_backorder - Product actually went on backorder. This is the target value.

Using Machine Learning to Predict Backorders

Libraries

We’ll use the following libraries:

tidyquant: Used to quickly load the “tidyverse” (dplyr, tidyr, ggplot, etc) along with custom, business-report-friendly ggplot themes. Also great for time series analysis (not featured)unbalanced: Contains various methods for working with unbalanced data. We’ll use the ubSMOTE() function.h2o: Go-to package for implementing professional grade machine learning.

Note on H2O: You’ll want to install the latest stable R version from H2O.ai. If you have issues in this post, you probably did not follow these steps:

- Go to H2O.ai’s download page

- Under H2O, select “Latest Stable Release”

- Click on the “Install in R” tab

- Follow instructions exactly.

Load the libraries.

# You can install these from CRAN using install.packages()

library(tidyquant) # Loads tidyverse and custom ggplot themes

library(unbalanced) # Methods for dealing with unbalanced data sets

# Follow instructions for latest stable release, don't just install from CRAN

library(h2o) # Professional grade ML

Load Data

Use read_csv() to load the training and test data.

# Load training and test sets

train_raw_df <- read_csv("data/Kaggle_Training_Dataset_v2.csv")

test_raw_df <- read_csv("data/Kaggle_Test_Dataset_v2.csv")

Inspect Data

Inspecting the head and tail, we can get an idea of the data set. There’s some sporadic NA values in the “lead_time” column along with -99 values in the two supplier performance columns.

# Head

train_raw_df %>% head() %>% knitr::kable()

| sku |

national_inv |

lead_time |

in_transit_qty |

forecast_3_month |

forecast_6_month |

forecast_9_month |

sales_1_month |

sales_3_month |

sales_6_month |

sales_9_month |

min_bank |

potential_issue |

pieces_past_due |

perf_6_month_avg |

perf_12_month_avg |

local_bo_qty |

deck_risk |

oe_constraint |

ppap_risk |

stop_auto_buy |

rev_stop |

went_on_backorder |

| 1026827 |

0 |

NA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

No |

0 |

-99.00 |

-99.00 |

0 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1043384 |

2 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

No |

0 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1043696 |

2 |

NA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

No |

0 |

-99.00 |

-99.00 |

0 |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1043852 |

7 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

No |

0 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

0 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1044048 |

8 |

NA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

No |

0 |

-99.00 |

-99.00 |

0 |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1044198 |

13 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

No |

0 |

0.82 |

0.87 |

0 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

The tail shows another issue, the last row is NA values.

# Tail

train_raw_df %>% tail() %>% knitr::kable()

| sku |

national_inv |

lead_time |

in_transit_qty |

forecast_3_month |

forecast_6_month |

forecast_9_month |

sales_1_month |

sales_3_month |

sales_6_month |

sales_9_month |

min_bank |

potential_issue |

pieces_past_due |

perf_6_month_avg |

perf_12_month_avg |

local_bo_qty |

deck_risk |

oe_constraint |

ppap_risk |

stop_auto_buy |

rev_stop |

went_on_backorder |

| 1407754 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

0 |

No |

0 |

0.69 |

0.69 |

5 |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1373987 |

-1 |

NA |

0 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

8 |

0 |

No |

0 |

-99.00 |

-99.00 |

1 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1524346 |

-1 |

9 |

0 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

0 |

8 |

11 |

12 |

0 |

No |

0 |

0.86 |

0.84 |

1 |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

| 1439563 |

62 |

9 |

16 |

39 |

87 |

126 |

35 |

63 |

153 |

205 |

12 |

No |

0 |

0.86 |

0.84 |

6 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| 1502009 |

19 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

7 |

12 |

20 |

1 |

No |

0 |

0.73 |

0.78 |

1 |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

| NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

If we take a look at the distribution of the target, train_raw_df$went_on_backorder, we see that the data set is severely imbalanced. We’ll need a strategy to balance the data set if we want to get maximum model performance and efficiency.

# Unbalanced data set

train_raw_df$went_on_backorder %>% table() %>% prop.table()

## .

## No Yes

## 0.993309279 0.006690721

We can also inspect missing values. Because both the train and test sets have missing values, we’ll need to come up with a strategy to deal with them.

# train set: Percentage of complete cases

train_raw_df %>% complete.cases() %>% sum() / nrow(train_raw_df)

## [1] 0.9402238

The test set has a similar distribution.

# test set: Percentage of complete cases

test_raw_df %>% complete.cases() %>% sum() / nrow(test_raw_df)

## [1] 0.939172

Finally, it’s also worth taking a glimpse of the data. We can quickly see:

- We have some character columns with Yes/No values.

- The “perf_” columns have -99 values, which reflect missing data.

glimpse(train_raw_df)

## Observations: 1,687,861

## Variables: 23

## $ sku <int> 1026827, 1043384, 1043696, 1043852, 104...

## $ national_inv <int> 0, 2, 2, 7, 8, 13, 1095, 6, 140, 4, 0, ...

## $ lead_time <int> NA, 9, NA, 8, NA, 8, NA, 2, NA, 8, 2, N...

## $ in_transit_qty <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ forecast_3_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 15, 0, 0, 0, 0,...

## $ forecast_6_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 114, 0, 0, 0, 0...

## $ forecast_9_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 152, 0, 0, 0, 0...

## $ sales_1_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ sales_3_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ sales_6_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ sales_9_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ min_bank <int> 0, 0, 0, 1, 2, 0, 4, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ potential_issue <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No...

## $ pieces_past_due <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ perf_6_month_avg <dbl> -99.00, 0.99, -99.00, 0.10, -99.00, 0.8...

## $ perf_12_month_avg <dbl> -99.00, 0.99, -99.00, 0.13, -99.00, 0.8...

## $ local_bo_qty <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ deck_risk <chr> "No", "No", "Yes", "No", "Yes", "No", "...

## $ oe_constraint <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No...

## $ ppap_risk <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No...

## $ stop_auto_buy <chr> "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes", "Yes...

## $ rev_stop <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No...

## $ went_on_backorder <chr> "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No", "No...

Data Setup

Validation Set

We have a training and a test set, but we’ll need a validation set to assist with modeling. We can perform a random 85/15 split of the training data.

# Train/Validation Set Split

split_pct <- 0.85

n <- nrow(train_raw_df)

sample_size <- floor(split_pct * n)

set.seed(159)

idx_train <- sample(1:n, size = sample_size)

valid_raw_df <- train_raw_df[-idx_train,]

train_raw_df <- train_raw_df[idx_train,]

Data Pre-Processing

Pre-processing includes a number of steps to get the raw data ready for modeling. We can make a pre-process function that drops unnecessary columns, deals with NA values, converts Yes/No data to 1/0, and converts the target to a factor. These are all standard pre-processing steps that will need to be applied to each of the data sets.

# Custom pre-processing function

preprocess_raw_data <- function(data) {

# data = data frame of backorder data

data %>%

select(-sku) %>%

drop_na(national_inv) %>%

mutate(lead_time = ifelse(is.na(lead_time), -99, lead_time)) %>%

mutate_if(is.character, .funs = function(x) ifelse(x == "Yes", 1, 0)) %>%

mutate(went_on_backorder = as.factor(went_on_backorder))

}

# Apply the preprocessing steps

train_df <- preprocess_raw_data(train_raw_df)

valid_df <- preprocess_raw_data(valid_raw_df)

test_df <- preprocess_raw_data(test_raw_df)

# Inspect the processed data

glimpse(train_df)

## Observations: 1,434,680

## Variables: 22

## $ national_inv <int> 275, 9, 6, 5, 737, 3, 318, 12, 66, 16, ...

## $ lead_time <dbl> 8, 8, 2, 4, 2, 8, 8, 2, 8, 9, 8, 2, 4, ...

## $ in_transit_qty <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 16, 0, 21, 0, 8, 5, 0...

## $ forecast_3_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 234, 0, 29, 0, 40, 14...

## $ forecast_6_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 552, 0, 62, 0, 80, 21...

## $ forecast_9_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 780, 0, 106, 0, 116, ...

## $ sales_1_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 129, 0, 10, 0, 19, 4,...

## $ sales_3_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 1, 409, 0, 35, 0, 50, 10...

## $ sales_6_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 5, 1, 921, 0, 57, 0, 111, 1...

## $ sales_9_month <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 9, 1, 1404, 2, 99, 0, 162, ...

## $ min_bank <int> 0, 2, 0, 0, 3, 1, 108, 1, 22, 0, 72, 2,...

## $ potential_issue <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ pieces_past_due <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ perf_6_month_avg <dbl> 0.96, 0.42, 1.00, 0.77, 0.00, 0.75, 0.7...

## $ perf_12_month_avg <dbl> 0.94, 0.36, 0.98, 0.80, 0.00, 0.74, 0.4...

## $ local_bo_qty <int> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ deck_risk <dbl> 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, ...

## $ oe_constraint <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ ppap_risk <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ stop_auto_buy <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...

## $ rev_stop <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...

## $ went_on_backorder <fctr> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,...

A step may be needed to transform (normalize, center, scale, apply PCA, etc) the data especially if using deep learning as a classification method. In our case, overall performance actually decreased when transformation was performed. We skip this step because of this. Interested readers may wish to explore the recipes package for creating and applying ML pre-processing recipes, which has great documentation.

Balance Dataset with SMOTE

As we saw previously, the data is severely unbalanced with only 0.7% of cases being positive (went_on_backorder = Yes). To deal with this class imbalance, we’ll implement a technique called SMOTE (synthetic minority over-sampling technique), which oversamples the minority class by generating synthetic minority examples in the neighborhood of observed ones. In other words, it shrinks the prevalence of the majority class (under sampling) while simultaneously synthetically increasing the prevalence of the minority class using a k-nearest neighbors approach (over sampling via knn). The great thing is that SMOTE can improve classifier performance (due to better classifier balance) and improve efficiency (due to smaller but focused training set) at the same time (win-win)!

The ubSMOTE() function from the unbalanced package implements SMOTE (along with a number of other sampling methods such as over, under, and several advanced methods). We’ll setup the following arguments:

perc.over = 200: This is the percent of new instances generated for each rare instance. For example, if there were only 5 rare cases, the 200% percent over will synthetically generate and additional 10 rare cases.perc.under = 200: The percentage of majority classes selected for each SMOTE observations. If 10 additional observations were created through the SMOTE process, 20 majority cases would be sampled.k = 5: The number of nearest neighbors to select when synthetically generating new observations.

# Use SMOTE sampling to balance the dataset

input <- train_df %>% select(-went_on_backorder)

output <- train_df$went_on_backorder

train_balanced <- ubSMOTE(input, output, perc.over = 200, perc.under = 200, k = 5)

We need to recombine the results into a tibble. Notice there are now only 68K observations versus 1.4M previously. This is a good indication that SMOTE worked correctly. As an added benefit, the training set size has shrunk which will make the model training significantly faster.

# Recombine the synthetic balanced data

train_df <- bind_cols(as.tibble(train_balanced$X), tibble(went_on_backorder = train_balanced$Y))

train_df

## # A tibble: 67,669 x 22

## national_inv lead_time in_transit_qty forecast_3_month

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 141.000000 -99.000000 0 0.00000

## 2 108.000000 8.000000 0 0.00000

## 3 38.000000 8.000000 0 26.00000

## 4 0.000000 -99.000000 0 0.00000

## 5 1.417421 11.165158 0 40.60803

## 6 253.000000 8.000000 11 175.00000

## 7 67.000000 52.000000 0 0.00000

## 8 0.000000 2.000000 0 5.00000

## 9 5.000000 12.000000 0 0.00000

## 10 0.000000 6.068576 0 24.19806

## # ... with 67,659 more rows, and 18 more variables:

## # forecast_6_month <dbl>, forecast_9_month <dbl>,

## # sales_1_month <dbl>, sales_3_month <dbl>, sales_6_month <dbl>,

## # sales_9_month <dbl>, min_bank <dbl>, potential_issue <dbl>,

## # pieces_past_due <dbl>, perf_6_month_avg <dbl>,

## # perf_12_month_avg <dbl>, local_bo_qty <dbl>, deck_risk <dbl>,

## # oe_constraint <dbl>, ppap_risk <dbl>, stop_auto_buy <dbl>,

## # rev_stop <dbl>, went_on_backorder <fctr>

We can also check the new balance of Yes/No: It’s now 43% Yes to 57% No, which in theory should enable the classifier to better detect relationships with the positive (Yes) class.

# Inspect class balance after SMOTE

train_df$went_on_backorder %>% table() %>% prop.table()

## .

## 0 1

## 0.5714286 0.4285714

Modeling with h2o

Now we are ready to model. Let’s fire up h2o.

# Fire up h2o and turn off progress bars

h2o.init()

## Connection successful!

##

## R is connected to the H2O cluster:

## H2O cluster uptime: 27 seconds 221 milliseconds

## H2O cluster version: 3.15.0.4004

## H2O cluster version age: 1 month and 18 days

## H2O cluster name: H2O_started_from_R_mdanc_bpa702

## H2O cluster total nodes: 1

## H2O cluster total memory: 3.51 GB

## H2O cluster total cores: 8

## H2O cluster allowed cores: 8

## H2O cluster healthy: TRUE

## H2O Connection ip: localhost

## H2O Connection port: 54321

## H2O Connection proxy: NA

## H2O Internal Security: FALSE

## H2O API Extensions: Algos, AutoML, Core V3, Core V4

## R Version: R version 3.4.0 (2017-04-21)

h2o.no_progress()

The h2o package deals with H2OFrame (instead of data frame). Let’s convert.

# Convert to H2OFrame

train_h2o <- as.h2o(train_df)

valid_h2o <- as.h2o(valid_df)

test_h2o <- as.h2o(test_df)

We use the h2o.automl() function to automatically try a wide range of classification models. The most important arguments are:

training_frame: Supply our training data set to build models.validation_frame: Supply our validation data set to prevent models from overfittingleaderboard_frame: Supply our test data set, and models will be ranked based on performance on the test set.max_runtime_secs: Controls the amount of runtime for each model. Setting to 45 seconds will keep things moving but give each model a fair shot. If you want even higher accuracy you can try increasing the run time. Just be aware that there tends to be diminishing returns.

# Automatic Machine Learning

y <- "went_on_backorder"

x <- setdiff(names(train_h2o), y)

automl_models_h2o <- h2o.automl(

x = x,

y = y,

training_frame = train_h2o,

validation_frame = valid_h2o,

leaderboard_frame = test_h2o,

max_runtime_secs = 45

)

Extract our leader model.

automl_leader <- automl_models_h2o@leader

Making Predictions

We use h2o.predict() to make our predictions on the test set. The data is still stored as an h2o object, but we can easily convert to a data frame with as.tibble(). Note that the left column (“predict”) is the class prediction, and columns “p0” and “p1” are the probabilities.

pred_h2o <- h2o.predict(automl_leader, newdata = test_h2o)

as.tibble(pred_h2o)

## # A tibble: 242,075 x 3

## predict p0 p1

## <fctr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0 0.9838573 0.01614266

## 2 0 0.9378156 0.06218435

## 3 0 0.9663659 0.03363410

## 4 0 0.9233651 0.07663488

## 5 0 0.9192454 0.08075463

## 6 0 0.9159785 0.08402145

## 7 0 0.8662870 0.13371302

## 8 0 0.9833785 0.01662152

## 9 0 0.9805942 0.01940576

## 10 0 0.9162502 0.08374984

## # ... with 242,065 more rows

We use h2o.performance() to get performance-related information by passing the function the leader model and the test set in the same fashion as we did for the prediction. We’ll use the performance output to visualize ROC, AUC, precision and recall.

perf_h2o <- h2o.performance(automl_leader, newdata = test_h2o)

From the performance output we can get a number of key classifier metrics by threshold using h2o.metric().

# Getting performance metrics

h2o.metric(perf_h2o) %>%

as.tibble() %>%

glimpse()

## Observations: 400

## Variables: 20

## $ threshold <dbl> 0.9933572, 0.9855898, 0.9706335, ...

## $ f1 <dbl> 0.006659267, 0.008856089, 0.01174...

## $ f2 <dbl> 0.004179437, 0.005568962, 0.00741...

## $ f0point5 <dbl> 0.01637555, 0.02161383, 0.0282485...

## $ accuracy <dbl> 0.9889084, 0.9889043, 0.9888795, ...

## $ precision <dbl> 0.6000000, 0.5454545, 0.4444444, ...

## $ recall <dbl> 0.003348214, 0.004464286, 0.00595...

## $ specificity <dbl> 0.9999749, 0.9999582, 0.9999165, ...

## $ absolute_mcc <dbl> 0.04423925, 0.04861468, 0.0504339...

## $ min_per_class_accuracy <dbl> 0.003348214, 0.004464286, 0.00595...

## $ mean_per_class_accuracy <dbl> 0.5016616, 0.5022113, 0.5029344, ...

## $ tns <dbl> 239381, 239377, 239367, 239353, 2...

## $ fns <dbl> 2679, 2676, 2672, 2660, 2653, 264...

## $ fps <dbl> 6, 10, 20, 34, 45, 56, 77, 97, 10...

## $ tps <dbl> 9, 12, 16, 28, 35, 39, 46, 56, 63...

## $ tnr <dbl> 0.9999749, 0.9999582, 0.9999165, ...

## $ fnr <dbl> 0.9966518, 0.9955357, 0.9940476, ...

## $ fpr <dbl> 2.506402e-05, 4.177336e-05, 8.354...

## $ tpr <dbl> 0.003348214, 0.004464286, 0.00595...

## $ idx <int> 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10,...

ROC Curve

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a graphical method that pits the true positive rate (y-axis) against the false positive rate (x-axis). The benefit to the ROC curve is two-fold:

- We can visualize how the binary classification model compares to randomly guessing

- We can calculate AUC (Area Under the Curve), which is a method to compare models (perfect classification = 1).

Let’s review the ROC curve for our model using h2o. The red dotted line is what you could theoretically achieve by randomly guessing.

# Plot ROC Curve

left_join(h2o.tpr(perf_h2o), h2o.fpr(perf_h2o)) %>%

mutate(random_guess = fpr) %>%

select(-threshold) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = fpr)) +

geom_area(aes(y = tpr, fill = "AUC"), alpha = 0.5) +

geom_point(aes(y = tpr, color = "TPR"), alpha = 0.25) +

geom_line(aes(y = random_guess, color = "Random Guess"), size = 1, linetype = 2) +

theme_tq() +

scale_color_manual(

name = "Key",

values = c("TPR" = palette_dark()[[1]],

"Random Guess" = palette_dark()[[2]])

) +

scale_fill_manual(name = "Fill", values = c("AUC" = palette_dark()[[5]])) +

labs(title = "ROC Curve",

subtitle = "Model is performing much better than random guessing") +

annotate("text", x = 0.25, y = 0.65, label = "Better than guessing") +

annotate("text", x = 0.75, y = 0.25, label = "Worse than guessing")

We can also get the AUC of the test set using h2o.auc(). To give you an idea, the best Kaggle data scientists are getting AUC = 0.95. At AUC = 0.92, our automatic machine learning model is in the same ball park as the Kaggle competitors, which is quite impressive considering the minimal effort to get to this point.

# AUC Calculation

h2o.auc(perf_h2o)

## [1] 0.9242604

The Cutoff (Threshold)

The cutoff (also known as threshold) is the value that divides the predictions. If we recall, the prediction output has three columns: “predict”, “p0”, and “p1”. The first column, “predict” (model predictions) uses an automatically determined threshold value as the cutoff. Everything above is classified as “Yes” and below as “No”.

# predictions are based on p1_cutoff

as.tibble(pred_h2o)

## # A tibble: 242,075 x 3

## predict p0 p1

## <fctr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0 0.9838573 0.01614266

## 2 0 0.9378156 0.06218435

## 3 0 0.9663659 0.03363410

## 4 0 0.9233651 0.07663488

## 5 0 0.9192454 0.08075463

## 6 0 0.9159785 0.08402145

## 7 0 0.8662870 0.13371302

## 8 0 0.9833785 0.01662152

## 9 0 0.9805942 0.01940576

## 10 0 0.9162502 0.08374984

## # ... with 242,065 more rows

How is the Cutoff Determined?

The algorithm uses the threshold at the best F1 score to determine the optimal value for the cutoff.

# Algorithm uses p1_cutoff that maximizes F1

h2o.F1(perf_h2o) %>%

as.tibble() %>%

filter(f1 == max(f1))

## # A tibble: 1 x 2

## threshold f1

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.6300685 0.2844262

We could use a different threshold if we like, which can change depending on your goal (e.g. maximize recall, maximize precision, etc). For a full list of thresholds, we can inspect the “metrics” slot that is inside the perf_h2o object.

# Full list of thresholds at various performance metrics

perf_h2o@metrics$max_criteria_and_metric_scores

## Maximum Metrics: Maximum metrics at their respective thresholds

## metric threshold value idx

## 1 max f1 0.630068 0.284426 64

## 2 max f2 0.560406 0.366587 86

## 3 max f0point5 0.719350 0.271677 41

## 4 max accuracy 0.993357 0.988908 0

## 5 max precision 0.993357 0.600000 0

## 6 max recall 0.000210 1.000000 399

## 7 max specificity 0.993357 0.999975 0

## 8 max absolute_mcc 0.603170 0.287939 72

## 9 max min_per_class_accuracy 0.254499 0.850965 207

## 10 max mean_per_class_accuracy 0.222498 0.853464 222

Is cutoff at max F1 what we want? Probably not as we’ll see next.

Optimizing the Model for Expected Profit

In the business context we need to decide what cutoff (threshold of probability to assign yes/no) to use: Is the “p1” cutoff >= 0.63 (probability above which predict “Yes”) adequate? The answer lies in the balance between the cost of inventorying incorrect product (low precision) versus the cost of the lost customer (low recall):

-

Precision: When model predicts yes, how often is the actual value yes. If we implement a high precision (low recall) strategy then we need to accept a tradeoff of letting the model misclassify actual yes values to decrease the number of incorrectly predicted yes values.

-

Recall: When actual is yes, how often does the model predict yes. If we implement a high recall (low precision) strategy then we need to accept a tradeoff of letting the model increase the no values incorrectly predicted as yes values.

Effect of Precision and Recall on Business Strategy

By shifting the cutoff, we can control the precision and recall and this has major effect on the business strategy. As the cutoff increases, the model becomes more conservative being very picky about what it classifies as went_on_backorder = Yes.

# Plot recall and precision vs threshold, visualize inventory strategy effect

left_join(h2o.recall(perf_h2o), h2o.precision(perf_h2o)) %>%

rename(recall = tpr) %>%

gather(key = key, value = value, -threshold) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = threshold, y = value, color = key)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.5) +

scale_color_tq() +

theme_tq() +

labs(title = 'Precision and Recall vs Cutoff ("Yes" Threshold)',

subtitle = "As the cutoff increases from zero, inventory strategy becomes more conservative",

caption = "Deciding which cutoff to call YES is highly important! Don't just blindly use 0.50.",

x = 'Cutoff (Probability above which we predict went_on_backorder = "Yes")',

y = "Precision and Recall Values"

) +

# p>=0

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 0.12, y = 0.75, size = 3,

label = 'p1 >= 0: "Yes"\nInventory\nEverything') +

geom_segment(x = 0, y = 0.7, xend = 0.02, yend= 0.72, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

# p>=0.25

geom_vline(xintercept = 0.25, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 0.37, y = 0.35, size = 3,

label = 'p1 >= 0.25: "Yes"\nInventory Anything\nWith Chance\nof Backorder') +

geom_segment(x = 0.25, y = 0.30, xend = 0.27, yend= 0.32, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

# p>=0.5

geom_vline(xintercept = 0.5, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 0.62, y = 0.75, size = 3,

label = 'p1 >= 0.50: "Yes"\nInventory\nProbability\nSplit 50/50') +

geom_segment(x = 0.5, y = 0.70, xend = 0.52, yend= 0.72, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

# p>=0.75

geom_vline(xintercept = 0.75, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 0.87, y = 0.75, size = 3,

label = 'p1 >= 0.75: "Yes"\nInventory Very\nConservatively\n(Most Likely Backorder)') +

geom_segment(x = 0.75, y = 0.70, xend = 0.77, yend= 0.72, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

# p>=1

geom_vline(xintercept = 1, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1) +

annotate("text", x = 0.87, y = 0.22, size = 3,

label = 'p1 >= 1.00: "Yes"\nInventory Nothing') +

geom_segment(x = 1.00, y = 0.23, xend = 0.98, yend= 0.21, color = palette_light()[[3]], size = 1)

Expected Value Framework

We need another function to help us determine which values of cutoff to use, and this comes from the Expected Value Framework described in Data Science for Business.

Source: Data Science for Business

To implement this framework we need two things:

- Expected Rates (matrix of probabilities): Needed for each threshold

- Cost/Benefit Information: Needed for each observation

Expected Rates

We have the class probabilities and rates from the confusion matrix, and we can retrieve this using the h2o.confusionMatrix() function.

# Confusion Matrix, p1_cutoff = 0.63

h2o.confusionMatrix(perf_h2o)

## Confusion Matrix (vertical: actual; across: predicted) for max f1 @ threshold = 0.630068453397666:

## 0 1 Error Rate

## 0 235796 3591 0.015001 =3591/239387

## 1 1647 1041 0.612723 =1647/2688

## Totals 237443 4632 0.021638 =5238/242075

The problems are:

- The confusion matrix is for just one specific cutoff. We want to evaluate for all of the potential cutoffs to determine which strategy is best.

- We need to convert to expected rates, as shown in the Figure 7-2 diagram.

Luckily, we can retrieve the rates by cutoff conveniently using h2o.metric(). Huzzah!

# Get expected rates by cutoff

expected_rates <- h2o.metric(perf_h2o) %>%

as.tibble() %>%

select(threshold, tpr, fpr, fnr, tnr)

expected_rates

## # A tibble: 400 x 5

## threshold tpr fpr fnr tnr

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.9933572 0.003348214 2.506402e-05 0.9966518 0.9999749

## 2 0.9855898 0.004464286 4.177336e-05 0.9955357 0.9999582

## 3 0.9706335 0.005952381 8.354673e-05 0.9940476 0.9999165

## 4 0.9604183 0.010416667 1.420294e-04 0.9895833 0.9998580

## 5 0.9513270 0.013020833 1.879801e-04 0.9869792 0.9998120

## 6 0.9423699 0.014508929 2.339308e-04 0.9854911 0.9997661

## 7 0.9320206 0.017113095 3.216549e-04 0.9828869 0.9996783

## 8 0.9201693 0.020833333 4.052016e-04 0.9791667 0.9995948

## 9 0.9113555 0.023437500 4.511523e-04 0.9765625 0.9995488

## 10 0.9061218 0.025297619 5.472311e-04 0.9747024 0.9994528

## # ... with 390 more rows

The cost-benefit matrix is a business assessment of the cost and benefit for each of four potential outcomes:

-

True Negative (benefit): This is the benefit from a SKU that is correctly predicted as not backordered. The benefit is zero because a customer simply does not buy this item (lack of demand).

-

True Positive (benefit): This is the benefit from a SKU that is correctly predicted as backorder and the customer needs this now. The benefit is the profit from revenue. For example, if the item price is $1000 and the cost is $600, the unit profit is $400.

-

False Positive (cost): This is the cost associated with incorrectly classifying a SKU as backordered when demand is not present. The is the warehousing and inventory related cost. For example, if the item costs $10/unit to inventory, which would have otherwise not have occurred.

-

False Negative (cost): This is the cost associated with incorrectly classifying a SKU when demand is present. In our case, no money was spent and nothing was gained.

The cost-benefit information is needed for each decision pair. If we take one SKU, say the first prediction from the test set, we have an item that was predicted to NOT be backordered (went_on_backorder == "No"). If hypothetically the value for True Positive (benefit) is $400/unit in profit from correctly predict a backorder and the False Positive (cost) of accidentally inventorying and item that was not backordered is $10/unit then a data frame can be be structured like so.

# Cost/benefit info codified for first item

first_item <- pred_h2o %>%

as.tibble() %>%

slice(1) %>%

add_column(

cb_tn = 0,

cb_tp = 400,

cb_fp = -10,

cb_fn = 0

)

first_item

## # A tibble: 1 x 7

## predict p0 p1 cb_tn cb_tp cb_fp cb_fn

## <fctr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0 0.9838573 0.01614266 0 400 -10 0

Optimization: Single Item

The expected value equation generalizes to:

\[EV = \sum_{i=1}^{N} p_i*v_i\]

Where,

- pi is the probability of the outcome for one observation

- vi is the value of the outcome for one observation

The general form isn’t very useful, but from it we can create an Expected Profit equation using a basic rule of probability p(x,y) = p(y)*p(x|y) that combines both the Expected Rates (2x2 matrix of probabilities after normalization of Confusion Matrix) and a Cost/Benefit Matrix (2x2 matrix with expected costs and benefits). Refer to Data Science for Business for the proof.

\[EP = p(p)*[p(Y|p)*b(Y,p)+p(N|p)*c(N,p)]\\

+ p(n)*[p(N|n)*b(N,n)+p(Y|n)*c(Y,n)]\]

Where,

- p(p) is the confusion matrix positive class prior (probability of actual yes / total)

- p(n) is the confusion matrix positive class prior (probability of actual no / total = 1 - positive class prior)

- p(Y|p) is the True Positive Rate (

tpr)

- p(N|p) is the False Negative Rate (

fnr)

- p(N|n) is the True Negative Rate (

tnr)

- p(Y|n) is the False Positive Rate (

fpr)

- b(Y,p) is the benefit from true positive (

cb_tp)

- c(N,p) is the cost from false negative (

cb_fn)

- b(N,n) is the benefit from true negative (

cb_tn)

- c(Y,n) is the cost from false positive (

cb_fp)

This equation simplifies even further since we have a case where cb_tn and cb_fn are both zero.

\[EP = p(p)*[p(Y|p)*b(Y,p)] + p(n)*[p(Y|n)*c(Y,n)]\]

We create a function to calculate the expected profit using the probability of a positive case (positive prior, p1), the cost/benefit of a true positive (cb_tp), and the cost/benefit of a false positive (cb_fp). We’ll take advantage of the expected_rates data frame we previously created, which contains the true positive rate and false positive rate for each threshold (400 thresholds in the range of 0 and 1).

# Function to calculate expected profit

calc_expected_profit <- function(p1, cb_tp, cb_fp) {

# p1 = Set of predictions with "predict", "p0", and "p1" columns

# cb_tp = Benefit (profit) from true positive (correctly identifying backorder)

# cb_fp = Cost (expense) from false negative (incorrectly inventorying)

tibble(

p1 = p1,

cb_tp = cb_tp,

cb_fp = cb_fp

) %>%

# Add in expected rates

mutate(expected_rates = list(expected_rates)) %>%

unnest() %>%

mutate(

expected_profit = p1 * (tpr * cb_tp) + (1 - p1) * (fpr * cb_fp)

) %>%

select(threshold, expected_profit)

}

We can test the function for a hypothetical prediction that is unlikely to have a backorder (most common class). Setting p1 = 0.01 indicates the hypothetical SKU has a low probability. Continuing with the example case of $400/unit profit and $10/unit inventory cost, we can see that optimal threshold is approximately 0.4. Note that an inventory all items strategy (threshold = 0) would cause the company to lose money on low probability of backorder items (-$6/unit) and an inventory nothing strategy would result in no benefit but no loss ($0/unit).

# Investigate a expected profit of item with low probability of backorder

hypothetical_low <- calc_expected_profit(p1 = 0.01, cb_tp = 400, cb_fp = -10)

hypothetical_low_max <- filter(hypothetical_low, expected_profit == max(expected_profit))

hypothetical_low %>%

ggplot(aes(threshold, expected_profit, color = expected_profit)) +

geom_point() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = hypothetical_low_max$threshold, color = palette_light()[[1]]) +

theme_tq() +

scale_color_continuous(low = palette_light()[[1]], high = palette_light()[[2]]) +

labs(title = "Expected Profit Curve, Low Probability of Backorder",

subtitle = "When probability of backorder is low, threshold increases inventory conservatism",

caption = paste0('threshold @ max = ', hypothetical_low_max$threshold %>% round (2)),

x = "Cutoff (Threshold)",

y = "Expected Profit per Unit"

)

Conversely if we investigate a hypothetical item with high probability of backorder, we can see that it’s much more advantageous to have a loose strategy with respect to inventory conservatism. Notice the profit per-unit is 80% of the theoretical maximum profit (80% of $400/unit = $320/unit if “p1” = 0.8). The profit decreases to zero as the inventory strategy becomes more conservative.

# Investigate a expected profit of item with high probability of backorder

hypothetical_high <- calc_expected_profit(p1 = 0.8, cb_tp = 400, cb_fp = -10)

hypothetical_high_max <- filter(hypothetical_high, expected_profit == max(expected_profit))

hypothetical_high %>%

ggplot(aes(threshold, expected_profit, color = expected_profit)) +

geom_point() +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, color = "red") +

geom_vline(xintercept = hypothetical_high_max$threshold, color = palette_light()[[1]]) +

theme_tq() +

scale_color_continuous(low = palette_light()[[1]], high = palette_light()[[2]]) +

labs(title = "HExpected Profit Curve, High Probability of Backorder",

subtitle = "When probability of backorder is high, ",

caption = paste0('threshold @ max = ', hypothetical_high_max$threshold %>% round (2))

)

Let’s take a minute to digest what’s going on in both the high and low expected profit curves. Units with low probability of backorder (the majority class) will tend to increase the cutoff while units with high probability will tend to lower the cutoff. It’s this balance or tradeoff that we need to scale to understand the full picture.

Optimization: Multi-Item

Now the fun part, scaling the optimization to multiple products. Let’s analyze a simplified case: 10 items with varying backorder probabilities, benefits, costs, and safety stock levels. In addition, we’ll include a backorder purchase quantity with logic of 100% safety stock (meaning items believed to be backordered will have an additional quantity purchased equal to that of the safety stock level). We’ll investigate optimal stocking level for this subset of items to illustrate scaling the analysis to find the global optimized cutoff (threshold).

# Ten Hypothetical Items

ten_items <- tribble(

~"item", ~"p1", ~"cb_tp", ~"cb_fp", ~"safety_stock",

1, 0.02, 10, -0.75, 100,

2, 0.09, 7.5, -0.75, 35,

3, 0.65, 8.5, -0.75, 75,

4, 0.01, 25, -2.5, 50,

5, 0.10, 15, -0.5, 150,

6, 0.09, 400, -25, 5,

7, 0.05, 17.5, -5, 25,

8, 0.01, 200, -9, 75,

9, 0.11, 25, -2, 50,

10, 0.13, 11, -0.9, 150

)

ten_items

## # A tibble: 10 x 5

## item p1 cb_tp cb_fp safety_stock

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 0.02 10.0 -0.75 100

## 2 2 0.09 7.5 -0.75 35

## 3 3 0.65 8.5 -0.75 75

## 4 4 0.01 25.0 -2.50 50

## 5 5 0.10 15.0 -0.50 150

## 6 6 0.09 400.0 -25.00 5

## 7 7 0.05 17.5 -5.00 25

## 8 8 0.01 200.0 -9.00 75

## 9 9 0.11 25.0 -2.00 50

## 10 10 0.13 11.0 -0.90 150

We use purrr to map the calc_expected_profit() to each item, thus returning a data frame of expected profits per unit by threshold value. We unnest() to expand the data frame to one level enabling us to work with the expected profits and quantities. We then “extend” (multiply the unit expected profit by the backorder-prevention purchase quantity, which is 100% of safety stock level per our logic) to get total expected profit per unit.

# purrr to calculate expected profit for each of the ten items at each threshold

extended_expected_profit_ten_items <- ten_items %>%

# pmap to map calc_expected_profit() to each item

mutate(expected_profit = pmap(.l = list(p1, cb_tp, cb_fp), .f = calc_expected_profit)) %>%

unnest() %>%

rename(expected_profit_per_unit = expected_profit) %>%

# Calculate 100% safety stock repurchase and sell

mutate(expected_profit_extended = expected_profit_per_unit * 1 * safety_stock) %>%

select(item, p1, threshold, expected_profit_extended)

extended_expected_profit_ten_items

## # A tibble: 4,000 x 4

## item p1 threshold expected_profit_extended

## <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 1 0.02 0.9933572 0.06512208

## 2 1 0.02 0.9855898 0.08621537

## 3 1 0.02 0.9706335 0.11290693

## 4 1 0.02 0.9604183 0.19789417

## 5 1 0.02 0.9513270 0.24660013

## 6 1 0.02 0.9423699 0.27298466

## 7 1 0.02 0.9320206 0.31862027

## 8 1 0.02 0.9201693 0.38688435

## 9 1 0.02 0.9113555 0.43559030

## 10 1 0.02 0.9061218 0.46573090

## # ... with 3,990 more rows

We can visualize the expected profit curves for each item extended for backorder-prevention quantity to be purchased and sold (note that selling 100% is a simplifying assumption).

# Visualizing Expected Profit

extended_expected_profit_ten_items %>%

ggplot(aes(threshold, expected_profit_extended,

color = factor(item)),

group = item) +

geom_line(size = 1) +

theme_tq() +

scale_color_tq() +

labs(

title = "Expected Profit Curves, Modeling Extended Expected Profit",

subtitle = "Taking backorder-prevention purchase quantity into account weights curves",

color = "Item No."

)

Finally, we can aggregate the expected profit using a few dplyr operations. Visualizing the final curve exposes the optimal threshold.

# Aggregate extended expected profit by threshold

total_expected_profit_ten_items <- extended_expected_profit_ten_items %>%

group_by(threshold) %>%

summarise(expected_profit_total = sum(expected_profit_extended))

# Get maximum (optimal) threshold

max_expected_profit <- total_expected_profit_ten_items %>%

filter(expected_profit_total == max(expected_profit_total))

# Visualize the total expected profit curve

total_expected_profit_ten_items %>%

ggplot(aes(threshold, expected_profit_total)) +

geom_line(size = 1, color = palette_light()[[1]]) +

geom_vline(xintercept = max_expected_profit$threshold, color = palette_light()[[1]]) +

theme_tq() +

scale_color_tq() +

labs(

title = "Expected Profit Curve, Modeling Total Expected Profit",

subtitle = "Summing up the curves by threshold yields optimal strategy",

caption = paste0('threshold @ max = ', max_expected_profit$threshold %>% round (2))

)

Conclusions

This was a very technical and detailed post, and if you made it through congratulations! We covered automated machine learning with H2O, an efficient and high accuracy tool for prediction. We worked with an extremely unbalanced data set, showing how to use SMOTE to synthetically improve dataset balance and ultimately model performance. We spent a considerable amount of effort optimizing the cutoff (threshold) selection to maximize expected profit, which ultimately matters most to the bottom line. Hopefully you can see how data science and machine learning can be very beneficial to the business, enabling better decisions and ROI.

Business Science University

Enjoy data science for business? We do too. This is why we created Business Science University where we teach you how to do Data Science For Busines (#DS4B) just like us!

Our first DS4B course (HR 201) is now available!

Who is this course for?

Anyone that is interested in applying data science in a business context (we call this DS4B). All you need is basic R, dplyr, and ggplot2 experience. If you understood this article, you are qualified.

What do you get it out of it?

You learn everything you need to know about how to apply data science in a business context:

-

Using ROI-driven data science taught from consulting experience!

-

Solve high-impact problems (e.g. $15M Employee Attrition Problem)

-

Use advanced, bleeding-edge machine learning algorithms (e.g. H2O, LIME)

-

Apply systematic data science frameworks (e.g. Business Science Problem Framework)

About Business Science

Business Science specializes in “ROI-driven data science”. Our focus is machine learning and data science in business applications. We help businesses that seek to add this competitive advantage but may not have the resources currently to implement predictive analytics. Business Science works with clients primarily in small to medium size businesses, guiding these organizations in expanding predictive analytics while executing on ROI generating projects. Visit the Business Science website or contact us to learn more!